Dr Solomon Carter Fuller—The Original Dementia Disruptor

During Black History Month, Carl Case founder of Cultural Appropriate Resources, along with the members of Sheffield’s newly created ‘Memory Hub’, highlight the importance of celebrating the life and achievements of one of Alzheimer’s disease original ‘disrupters’, Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller.

Born in 1872 he was a close colleague of Alois Alzheimer, and is widely acknowledged as the first American psychiatrist of African descent, but largely underappreciated as a pioneer of Alzheimer's disease, researching and writing extensively and become a leading authority on the subject.

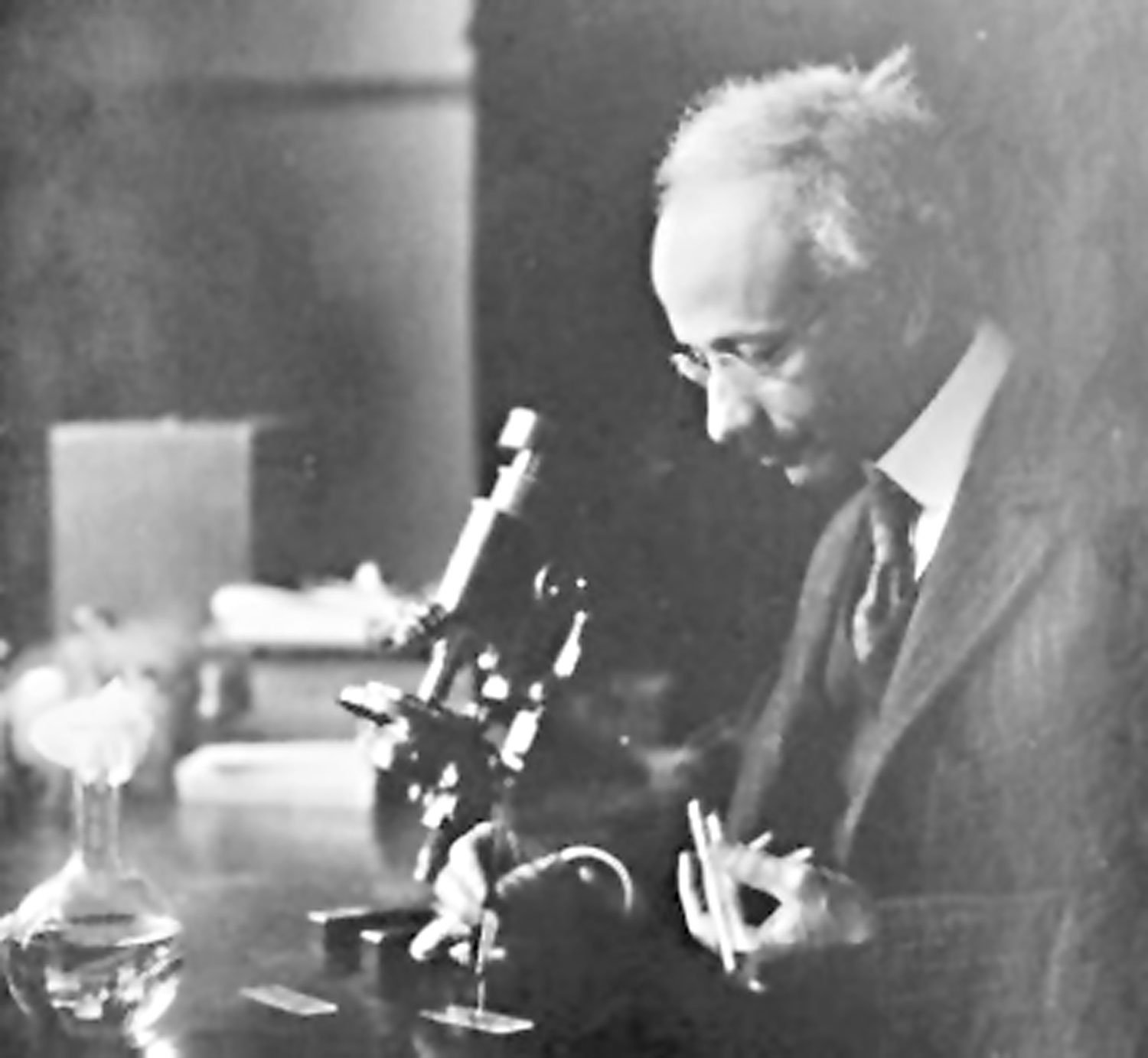

Dr Solomon Carter Fuller

West African Liberian born, Solomon was the grandson of enslaved American grandparents who purchased their freedom and left for Liberia under the American Colonization Fund. He migrated to the United States at age 17 and excelled in his medical career to become associate professor of both pathology and neurology at Boston University by 1921.

In 1904, Dr. Fuller sought to improve his laboratory and diagnostic skills by studying in Europe and was selected by Dr. Alzheimer to join his small team of five research assistants as he was studying what was called ‘presenile dementia’ at the time.

Dr. Fuller worked as a neuropathologist, performing anatomical and histological preparations at the Royal Psychiatric Hospital at the University of Munich. The hospital was headed by psychiatrist Dr. Emil Kraepelin, a renowned psychiatrist who coined the term "Alzheimer's disease" after his student, Alois Alzheimer.

On his return from Munich in 1907, Fuller published a case series describing the neuropathological features on autopsy of patients diagnosed with conditions including "dementia paralytica", "dementia senilis," and chronic alcoholism. In it he reported abnormal neuronal appearances and the presence of neurofibrils in cases of "dementia senilis" and "dementia paralytica", while also recognizing the influence of Kraepelin and Alzheimer in furthering his career in Germany and their input in dementia research to date.

Seated left to right, Dr. Alois Alzheimer, Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller New York Public Library Digital Collections

Fuller in 1911 was to publish one of the first studies to appraise the role of senile plaques in aging, supporting Alzheimer's observation in refuting the role of arteriosclerosis in plaque formation and questioned the importance of plaques and neurofibrillary pathology as hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease.

Dr Fuller's seminal piece came in 1912 when he,

Published, in two parts, the first comprehensive review of Alzheimer's disease at the time

Reviewed 11 known cases

Translating Alzheimer's original case in English for the first time

Described the ninth recorded case of the disease.

In the same year, alongside his colleague Henry Klopp, he described a case of suspected Alzheimer's disease that did not exhibit intracellular neurofibrils on autopsy, yet bore senile plaques and clinical similarities to previously diagnosed cases. Jointly recognising the case as “an example of the group now designated as Alzheimer's disease,” they unequivocally accepted Alzheimer's disease as a clinical entity but stopped short of regarding it distinct from senile dementia altogether.

Dr Fuller's patient was a 56-year-old man with a 2-year history of memory impairment, receptive dysphasia, and apraxia. Autopsy revealed “regional cerebral atrophies,” a degree of large vessel arteriosclerosis, extensive plaque presence, and intracellular "Alzheimer degeneration," comprising a “tangled mass of thick, darkly staining snarls and whirls of the intracellular fibrils,” reflective of neurofibrillary tangles.

“With the sort of work that I have done, I might have gone farther and reached a higher plane had it not been for the colour of my skin”

He became associate professor of neuropathology at Boston University later associate professor of neurology, however found himself on the receiving end of racial discrimination and being paid less than his fellow white professors. Between 1928 and 1933, he acted as chair of the Department of Neurology yet was not actually afforded the title. He retired in 1933, at age 61, after a junior white assistant professor was promoted to full professorship and appointed the official departmental chair, a move Fuller felt may not have occurred had he been white.

In his own words, Fuller commented, “With the sort of work that I have done, I might have gone farther and reached a higher plane had it not been for the colour of my skin”. On retirement he was given the title of emeritus professor of neurology at Boston University.

Article written by Carl Case, Founder of Cultural Appropriate Resources

Biography

Carl's work focuses on empowering individuals, families and professionals facing the challenges of dementia, through support, training, accompanied with the development, sharing and delivery of innovative cultural responsive interventions and resources.